A psychological and pragmatic approach – Covid 19 relevant

Introduction

In these times many of us may suffer from different types of grief.

If we look at the definition of grief, we can define grief as the psychological-emotional experience following a loss of any kind (relationship, status, job, studying plans, home habits/comfort, game, income, etc).

Bereavement is a more specific type of grief related to someone dying.

Losing a loved one is one of the most distressing and stressful life events (Holmes and Raheand, 1970). Unfortunately, it is also one of the most common experiences we face as human beings. Nevertheless, most people experience normal bereavement with a period of sorrow, numbness, at times guilt and anger, but gradually these feelings ease and move towards full acceptance and recovery.

In this article we will look at 3 myths about grief, the main psychological stages of grieving, and how to offer support to those around us in these confusing and exceptional times where the comfort and the emotional support is particularly needed.

We will look more specifically at how we can offer support in 3 type of situations: in general experiences/perceptions of loss and related sadness, in the case someone we know has lost a closed one, and finally when complex grief occurs (because of underlying psychological factors, forced social isolation or inability to say goodbye for example which is commonly the case during covid19 crisis).

Three myths about grieving

Myth #1: Grief is an emotion.

Given that grief occurs in some of the most painful situations anyone can imagine, we generally associate it with depression. A common misconception is that it is simply a feeling that comes and goes. In reality, grief is a process that is composed of several emotions like sadness, ager, grief, shock, relief and sometimes the absence of emotions, (denial/numbness) which are normal, can all occur simultaneously, and in no specific order at all.

2. Myth #2: Grief (treating, expressing, showing or talking about it) is bad.

Researchers and psychologists recognize the grief process not only healthy but necessary (Zisook & Shear, 2009).

the process involves ajutement to change and we know it can take significant time to adjust to what has occurred by exploring essential questions such as: “Who am I without my loss? How would my loved one want me to feel? How can I best honor their memory?”

Many grief experts believe that one of the functions of grief is to provide an opportunity for us to answer questions like these, ultimately allowing us to honor loved ones and come naturally to acceptance and healthy integration.

Myth #3: There is a right way to grieve.

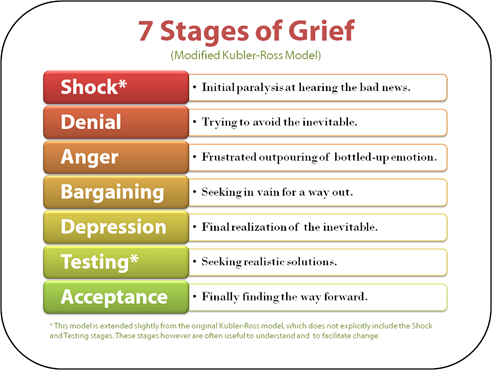

as we will see further, there are 5 stages to grief (sometimes broken down into 7), however these stages do not always imply a specific order. some can spend a significant time in the first stage of denial and others can reach the last stage of acceptance quite rapidly. We can likewise, move from stage 4 to 2 and come back to 4, we can skip stages, repeat stages, or even experience emotions not captured in the original five.

Since the order is irrelevant and the process very specific and personal for each individual we cannot expect a timeline, an order or a specific pattern of grieving.

Hence, it is important not to force yourself to fit someone else’s idea of what grief should look like.

The Stages of Grief

As discussed previously, everyone grieves differently. Despite a model of 7 stages, as stated previously, some will not experience all stages, a particular order or a specific way of displaying the emotions through the process.

Some individuals will wear their emotions “on their sleeve” and be outwardly emotional, talkative or explicit about what they need including reaching out for support.

Others will experience grief more internally, may not cry, may not even look sad or act “in a depressed way”. it it important not to judge how a person experiences grief, nor underestimate the impact of a loss, no matter what coping mechanisms they display.

when it comes to grief, there are also cultural differences to take into account. Some cultures embrace death, grief, and loss as a celebration and a normal part of life. Traditions may honor openly death with ceremonies, families or religious rituals which often allow to grieve in a community spirit and healthily, without the need to suppress or deny the pain. Such customs help in easing suffering to some degree.

When helping someone coping with grief, it may be helpful to be curious about personal traditions, customs and beliefs and help them incorporate these in finding meaning and customs that are helpful in giving and making sense of such losses. Although regular funerals procedures vary by country in the context of covi19 pandemic, for example it is common to be unable to burry someone as per tradition requirements, the philosophy behind and a later ceremony can be maintained.

Below a brief description of each stage / phase one can go when grieving.

- Shock & Denial & Isolation

This is the first reaction when finding out the news. We can tell ourselves things like: “This isn’t happening, this can’t be happening,” which is a normal reaction to rationalize overwhelming news.

Denial is common defense mechanism that buffers the immediate shock of the loss, numbing our emotions. We may hide from the facts, block words or refuse that conversation.

2. Anger

As reality starts to emerge, we may be faced with Anger. At objects, at ourselves or at deceased loved one for causing us pain or for leaving us. We feel guilty for being angry, and this makes us more angry.

we may choose to direct anger towards ourselves or towards doctors, towards government measures, towards someone we think may have contributed to the death (example contaminated with the virus or acted too late)

While doctors can seem a good target for relieving such overwhelming emotions, it is important to know that despite the fact that health professionals deal with death on a daily basis, this doesn’t make them immune to suffering or to what we call vicarious trauma (the indirect trauma that occurs as a result of being exposed, as a helping professional, to difficult experiences, images or stories in the process of helping).

3. Bargaining

“what if I had…” or “if they only hadn’t done this…”are typical reflections that try to postpone and deal with the inevitable reality. We may try to entertain beliefs about something we or others could have done differently to save the loved one. But in the end, things will not change and cannot replace the loss.

4. Depression

Sadness and regret characterize this type of depression. We worry that we have not spent enough time or helped the loved ones before the separation. we grieve not being able to say goodbye and ‘I love you’. These type of concerns are worthwhile exploring, discussing and clarifying via the support we can offer (see the tips below) or professional counselling.

5. Acceptance

This stage may not be accessible to everyone as anger and denial can linger when sudden/traumatic death occurred for example, and led to complex grief as explained further below.

it is important to know that this is not a period of happiness but is distinguishable form depression in the way that some sense of being able to function again, have hope for the future and inner peace is mostly reached.

while coping with loss is ultimately a deeply personal and intimate experience — nobody can make it easier for us as such or understand all our intimate emotions and processes, however we can accompany and comfort others through this process and offer our time and compassionate presence so they can allow themselves to feel it and eventually overcome it.

How to support someone dealing with grief

Supporting someone with a Perception / Experience of loss (job, finances, status, habits etc)

Since grief is a subjective and very personal experience, losing something that is not a closed one but rather a situation, an object or a position that has been beneficial to us so far, can also cause suffering, take one on a grief process and force them to adjust to this new and sudden change. The following actions can be taken to smooth someone’s experience and be there for them when needed:

- Help them understand the process of grief. You can share the infographic with them (or this article) and validate their experience by showing them you understand what it means and how it can affect someone.

- You can display this type of understanding further by sharing your own experiences of loss and how you felt. If they are similar type of losses (ex jobs), it is best.

- Accept there’s no right or wrong way to grieve and that there are no things that are more worthy than others to grieve upon. This attitude helps being in a non-judgmental space and a compassionate presence.

- Ask them to clarify their specific needs in the moment and later on. What can you do to help them.

- Check in with them often. It takes time to come to acceptance and motivation to start again or adapt and persevere, so show up at later moments too.

- Remind them you are there if they need to talk (without forgetting to check in for news regularly, which confirms your availability to be there and genuine caring)

- Offer them contacts of persons who might help them, answer their questions or concerns or professional help such as personal contacts, career counselling, coaching or therapy counselling. Offer concrete help in clarifying their situation and plans for worse case scenarios. Have the contacts handy.

- Do not offer advice on how to deal with things.

- Be a listening ear and refrain from trying to ”fixing it”, make them feel better, offer advice, solutions unless they ask you specifically.

- You may feel awkward in a first place or not strong enough to offer an emotional presence because of your own circumstances. Its ok, respect this and do not force yourself to be a support if you are struggling with your own grief. Express how you feel (powerless or sorry for not being of better help). Honesty helps actually more than pretending we are strong and ok (and possible making mistakes or creating misunderstandings).

- Do not distance yourself from them. Do not assume they need to be left in peace or that you would disturb them when reaching out. Keep doing the usual things with them (or scheduled things), it’s important.

- Offer an activity to do together, example watch an online movie /streaming, take walks together. A list of inspirational and life-changing movies can be found here and another one here.

- Be patient. Their behavior will not be the usual you know, be understanding and try not to take things personally.

Supporting someone with Complex Grief (CG)

Complex or complicated grief is a type of grief where symptoms linger or get worse over time instead of easing and leading to acceptance (normal grief process).

This type of grief can occur more particularly when we have troubles carrying out normal routines, isolate from others and withdraw from social activities (forced or chosen) or when we have been unable to say goodbye which are circumstances usually brought up by covid19 sanitary crisis.

Complex grief can also happen when we present with underlying psychological difficulties (such as depression or anxiety disorders) which can impede, postpone or aggravate the healthy grieving process. other characteristics of complex grief include experiences beliefs that we did something wrong (or could have prevented the death), struggling to find meaning to life without the loved one or as a consequence of losing them.

The importance of specialized and adequate and professional treatment is vital. Complicated grief usually responds well to a specific psychotherapy and is best when administered in combination with antidepressant medication as demonstrated in this study (ZISOOK & SHEAR, 2009). We can therefore encourage and accompany the person we want to support to take steps towards medical /psychiatric assistance or counselling. Besides the tips we suggested above we can add the following actions Do-s and DO NOT-s that are more relevant for traumatic or complex grief.

√ DO-s

- Help them connect with a group -counselling service designed for bereavement. Studies show that community-based group-therapy are effective in the long term and are highly suitable for Complex Grief (CG) situations. (Newsome et all, 2017). Covid19-specific services dedicated to families or survivors may also exist in your local area, strive to find the information from health authorities near you.

- Ask questions about the circumstances of the loss. Help them debrief if you can and explore the timeline of the tragedy. Last time they saw the deceased and after their death what did they do, what happened, etc – this brings them out of confusion although they may be highly anticipated questions for the person who asks.

- Listen and share memories. Doing so helps confirming the depth of their grief and keeps the love alive. Memories about their loved ones or your own memories and how you survived a loss.

- Avoid stereotyped statements such as: “Time heals all wounds” or “They are in a better place”. Research showed that they are not only unhelpful but can be extremely irritating to hear.

- Grievers may feel at times that by enjoying their life, they are betraying their lost loved one. They may refuse grief to end as a result, and feed maladaptive behaviors and belief that are typical of CG. Challenging their beliefs may be useful.

- Be an example yourself of someone who survived loss by talking about your experience. This demonstrates that grief is survivable and we can connect to life, hope and motivation over time.

- Offer your time well beyond the loss has occurred. In CG, grief process last over a year and can became more heavy; when loneliness, missing the person and adjusting to change become settle in their reality.

- Grievers prefer helpers to check in with them often rather than being told’ if you need anything, I am there’. Reach out and show up as often as you can.

- If talking about things is still difficult or complicated offer them a chance to write to you. Writing process allows them to separate themselves from the pain, understand better their emotions, slow down the mind and process things in a more objective way. New perspectives and insights come out as a result of journaling or writing/texting to someone.

- Grief is not only about dealing with the separation. It is also about seeking ways to maintain a sense of connection with the deceased. This is called grief integration as opposed to grief ” recovery “(as we do not usually recover or move on but integrate the loss and make it part of our growth journey). The connection can be maintained by thinking of ways to honor their life (by embodying they values and legacy for example) or by sharing memories of them with others regularly, lighting candles, going to the cemetery, or creating a special box with cherished symbols/objects that described the connection. Help them create a tangible ritual that can honor the loved one and maintain this sense of connection beyond the limits of reality and time.

- Suggest a letter to the deceased and ask them to think what would they respond if they were “here”.

- Offer practical help if necessary. Example do their admin, do a few calls for them, take the notes of classes, etc. Shock freezes the nervous system and makes us unable to attend to the basic needs, thrive to find out how you can help pragmatically.

- Offer to attend the ceremony and to be notified when it will be organized- it is highly appreciated

- Support and respect their cultural or spiritual beliefs and help them find meaning in their set of beliefs.

- Don’t be afraid to make them laugh (as well)! Grief doesn’t have to be a serious and sad process all along. Relativizing helps bring hope and remind the versatility and colourfulness of life. Offer enjoyable activities and respect their mood at that moment in time.

DO NOT-s

Do not state plenitudes such as:

“You’ll be ok, mate”

“Time heals all wounds”

“They are in a better place”

These statements although well intended, often fail to honor the depth of grief. While harmless for some, they can be more painful for others. Likewise, thrive to go beyond the ‘Sincere Condolences’ statement and use more meaningful ways to support as discussed in this article.

Do not avoid them.

Keep the contact with them as usual. They need you to show up possibly more than ever, so do stick around and be proactive as much as you can. We may often assume they need time and space, and that we may disturb. Research shows it is often not the case. Most givers prefer to know others stay around and keep reaching out.

Do not stop them crying.

Crying is a normal response to grief and sadness is a normal emotion. It is important to allow others (and ourselves) to grieve and be ok with tears and sadness, as they are healthy coping mechanisms and need to be normalized and respected.

Do not compare.

As discussed above, grieving a very individual process and cannot be compared with your responses or other people’s responses. Honor the uniqueness of each response and allow yourself to be unique and authentic in the expression of your sadness, feelings or impact this death may cause on you as well. Showing our humanity often helps in the most unexpected ways.

Don’t stop talking about it.

Do not be afraid to ask how they are feeling about the loss after you discussed the first time. It is usually reassuring to know we remember and follow up with things that matter. The subject does not have to remain taboo, on the contrary.

Conclusion

Losing someone is the most difficult human experience one can undergo. Knowing how to respond to losses for ourselves and for others is important in order to maintain a spirit of community and solidarity with each other, especially needed in times of sanitary and economic crisis like these.

Shocking and distressing events like grief, give us an opportunity to show up for each other, practice and cultivate the essential core values we thrive to embody such as compassion, patience, loyalty, team playing, genuine care and practical support.

In some ways, by allowing ourselves to grieve our possible losses, with a self-nurturing approach, we allow others to do so as well. A good starting point is to start practising this with ourselves in the process of meeting unprecedented challenges, concerns about the future, social and emotional isolation.

“The only constant is change. No matter how bad the situation is, do not worry, it will change. Nothing is permanent.” Buddha

In existential therapy, grief or the idea of death is explored as one of the 4 ultimate concerns of human beings. Yalom Irwin founded the existential therapy after Frankl’s existentialist philosophy – concentration camp survivor and psychiatrist. In 1980, Yalom defined the 4 ultimate human existential concerns that will always preoccupy one’s mind at one point in life: authenticity (or freedom of choice), death, the search for meaning and (existential) isolation (we are all ultimately alone in our subjective experience).

The goal for the death theme exploration in existential therapy is to raise awareness of the very reality of death so we can assess our priorities and lives accordingly, and live more fulfilling lives. We can like wisely create space for these reflections outside therapy and grow from each experience.